The Iran Deal (or the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action—JCPOA—as it is officially known) has now come up at both presidential debates and the only vice presidential debate. With its time in the spotlight renewed, it is worth returning to the run-up to the deal to examine how and why the United States and Iran got there. Iran’s need for a nuclear agreement is relatively straightforward given the economic impact of sanctions and the changing security dynamics of its region. While a deal could also have advantages for the United States, did it really need one the same way Iran did?

The debate surrounding an American need for a nuclear deal resurfaced in a May New York Times Magazine article, namely the assertion that the United States faced a choice between a deal or war. In my reading, this is a false dichotomy as it ignores a third, more likely outcome: nothing – Washington would take no action in response to Iran’s growing nuclear infrastructure, and Iran would slowly, eventually, acquire a nuclear capability and the world would learn to deal with it.

Neither alternative to a deal – war or a nuclear armed Iran – was preferable. Yet even with the nuclear agreement now in place, it is a mistake to think issues in the Middle East are even marginally less complicated for the United States. In effect, Washington traded a reduction in a theoretical existential threat to the United States with a low likelihood of occurring (a potential future Iranian nuclear strike on the United States) for an increase in high-likelihood conventional threats to the region (non-nuclear Iranian use of force in neighboring sovereign territory, as it has done in Lebanon, Syria, and Iraq). Though the United States has mitigated the rise of a potential nuclear power for the time being, the increase in regional conventional risk must be managed. It will not be easy.

The Iranian Case for a Deal

Iran’s case for a deal is clear given the incredible impact of international sanctions on Iran’s economy and Iran’s improving strategic position in the greater Middle East.

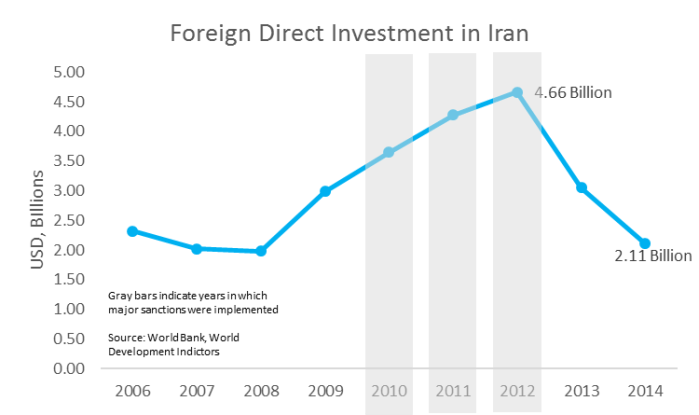

Sanctions devastated the Iranian economy after the European Union and United Nations joined the United States. in implementing more aggressive measures between 2010 and 2012. Iran’s GDP per capita fell a whopping 31 percent between 2011 and 2014, while oil exports—on which Iran’s government relies for 50-60 percent of its income—fell by nearly half during the same period. Just as critically, sanctions prevented Iran from accessing the Western technology and capital needed to modernize its ageing energy infrastructure and develop its massive, underutilized natural gas reserves (Iran is a net gas importer despite possessing one of the largest natural gas reserves in the world).

The impact of the 2010-2012 nuclear sanctions on Iran’s economy is striking when visualized. The following illustrate just how dramatically Iranian GDP, GDP per capita, and foreign direct investment were impacted:

Source: World Bank, World Development Indicators

Iran had an urgent economic need for a deal, but its changing strategic position in the region is what made giving up its nuclear program in exchange for sanctions relief palatable. The U.S. withdrawal from Iraq in 2011 and the U.S. draw-down in Afghanistan meant that, for first time in the Islamic Republic’s history, the country had no existential threat on its borders driving the need for a nuclear deterrent. Until 2003, Iran had to deter an aggressive neighbor in Saddam Hussein, who had already waged a costly war with Iran in 1980s and had proved willing to invade his neighbors (Kuwait), gas his own people with (the Kurds), and was developing a nuclear capability of his own into the 1990s. When Hussein fell, one potential threat replaced another. With the invasion of Iraq in 2003 and the onset of the war in Afghanistan in 2001, Iran found itself wedged between American conventional forces in Iraq in the west and in Afghanistan in the east. Iran’s insecure regional position created a strong need to develop a nuclear deterrent against the possibility of conventional attack.

But with the United States now out of Iraq and slimming its presence in Afghanistan, and with Iraq’s government in Baghdad now under Iranian influence, Iran found the threat of conventional invasion dramatically reduced. Conflict in the region now revolves around funding proxies and running irregular militias, something at which Iran excels. Giving up the nuclear program and its deterrent capability became an acceptable cost.

The U.S. Case for a Deal

The United States had been content to counter Iran’s nuclear program with sanctions for much of the 2000s. Why strike a deal now? From the U.S. perspective, the case for a deal is a function of time and resources.

Stepping back into the pre-9/11 world, before Islamist terrorism became the overriding—and often only—consideration in popular discourse about threats to American security, one sees just how seriously the United States took the threat of nuclear proliferation. Official American assessments of threats to national security in the post-Cold War world placed nuclear proliferation at the top of the list. Even after 9/11, fears that rogue states or non-state actors like al Qaeda could get their hands on nukes and other weapons of mass destruction continued to feature prominently in such assessments.

Nuclear proliferation is still a real risk, even if we sometimes forget about it in a world in which al Qaeda and the self-proclaimed Islamic State dominate headlines. The greater the number of states that possess nuclear weapons, the greater the odds that one of those states might use or lose track of one. The international effort to freeze the expansion of nuclear-capable states rests on the Nuclear Non-proliferation Treaty (NPT), to which Iran is a signatory. Allowing Iran, or any member country, to break its commitments to the NPT would undermine the NPT’s effectiveness in hindering proliferation, which the United States has a strong reason to prevent. If member states were to obtain nukes without consequence, every other member would have less reason to maintain its commitment to the agreement and a greater incentive, from a national security perspective, to obtain its own weapon as a deterrent.

Limiting the number of new states acquiring nuclear weapons is key to keeping the NPT from falling apart. But why strike a deal with Iran now?

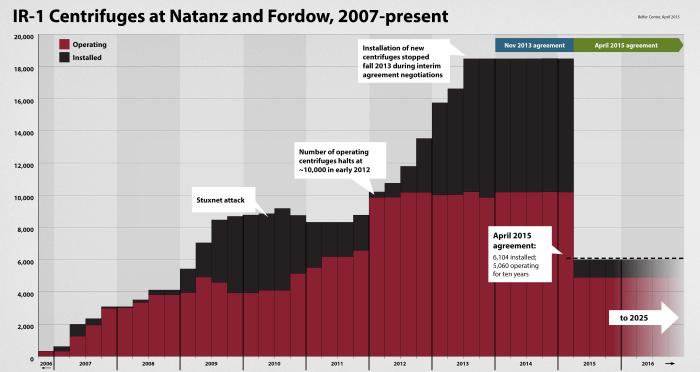

From 2006 until the interim nuclear agreement in November 2013, Iran had continuously installed new centrifuges for uranium enrichment—this despite American sanctions. By the time the interim deal was signed in 2013, most estimates pegged Iran’s breakout time between six weeks to two months. This means that Iran had installed enough centrifuges to, if it decided to go all-out and enrich uranium as quickly as its infrastructure would allow, without regard for secrecy, it would enrich half enough enriched uranium for a nuclear weapon in as a little as a month and a half. This does not mean Iran could create an actual nuclear weapon in six weeks (that still requires developing technology for the warhead itself, the delivery system, and other components), but it is a critical milestone.

The above graphic from the Belfer Center illustrates Iran’s continuous installation of centrifuges, the limits the JCPOA would impose on it (source: Belfer Center)

Iran narrowing the gap between potentially having enough material for a nuclear weapon and having it in reality is what pushed the United States to act. In a sense, the United States needed the deal because it addressed an essential security concern—nuclear proliferation—that demanded an immediate answer. The pressure to do something about Iran came to a head during 2012, a year that generated headlines like “The choice: should the US and Israel bomb Iran?” (Telegraph), “Time to Attack Iran” (Foreign Affairs), and “Twenty reasons not to attack Iran” (Reuters). But is the deal—this deal—the only way to prevent a nuclear Iran? A range of alternative measures were suggested, from the diplomatic to the kinetic.

Some critics simply suggested a “better” deal as one alternative, by which they mean a deal in which Iran gives up more (e.g. dismantles rather than repurposes certain infrastructure, an agreement term longer than ten years, etc.) and the United States gives up less (e.g. retaining sanctions on certain entities or an easier process to challenge Iran if they are suspected of cheating).

A new deal was likely impossible. We tend to forget that foreign governments must answer to their domestic constituencies, too, and Hassan Rouhani’s administration has invested a huge amount of political capital in the deal, fending off opposition politicians to push the deal forward. It is likely Rouhani would be unable to sustain his defense against those trying to sabotage diplomacy with the United States if forced to start again from scratch.

For perspective on the tough road Rouhani would face if the deal collapsed, recall that two previous presidents had already attempted outreach to the United States and failed. Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani (1989-1997) was a conservative pragmatist who in 1995 awarded the first Iranian oil contract to an American firm (Conoco, worth over $1 billion. President Clinton responded by banning investment in Iran’s oil sector and instituting new sanctions. The reformist upstart Mohammad Khatami (1997-2005), who upset the regime-favorite Nateq al-Nuri in the 1997 presidential elections, called for dialogue with America in a 1998 CNN interview, cooperated with the United States against the Taliban in Afghanistan after 9/11, and later offered to put the nuclear program on the negotiating table. But the Bush White House named Iran to the “Axis of Evil” in 2002, a public embarrassment to Khatami and his reformist movement. The conservative Mahmoud Ahmadinejad won Iran’s next presidential election; he is coincidently the only Iranian president since the death of Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini in 1989 to not attempt outreach to the United States.

Rouhani attempted outreach to the United States despite his predecessors’ failures attempting the same. It is highly unlikely he would have been able to start talks again if the deal failed, much less start brand new negotiations from scratch while giving up even more to the United States, as the deal’s American critics suggest.

Moreover, the United States faced the real risk that the sanctions regime weighing on Iran might crumble. The added weight of European Union and United Nations sanctions are what helped bring Iran to the negotiating table. The most recent sanctions have succeeded because they included three of Iran’s most important trading partners: Russia, China, and the European Union. Russia and China were key votes in favor of the suffocating UN sanctions enacted against Iran’s financial sector in 2010. In 2012 the EU banned the import of Iranian oil and levied sanctions against Iran’s central bank (the EU was the world’s largest importer of Iranian oil prior to the ban). If the talks these sanctions brought about failed, there was little reason to think Russia, China, and the EU would have the patience to continue enforcing them European businessmen started rushing back to Tehran as early as August 2015, and China was already offering “barter” deals for Iranian oil to circumvent sanction’s targeting Iran’s participation in the international banking system.

Waning European and Chinese tolerance for sanctions on badly-needed Iranian energy would leave the United States standing alone, trying to convince Iran to come back to the negotiating table as the regions that actually have influence over the Iranian economy—Europe and Asia—happily restored trade ties. The sanctions levied by the international community were essential to bringing Iran to the negotiating table, but those same sanctions effectively put an expiration date on the American opportunity to act.

How else could the United States deal with Iran in the absence of a new deal? Without a deal, Iran would resume building centrifuges and continue to narrow its breakout time until the window for action became so slim that the only remaining option to prevent Iran from acquiring enough nuclear material for a bomb was a destructive attack on Iran’s nuclear infrastructure.

To deny Iran the nuclear infrastructure for a nuclear weapon through airstrikes, the United States would need to commit to years of regular operations. Recent assessments suggest airstrikes would only set Iran’s nuclear program back by one or two years, and with each successive strike Iran’s resolve to develop a nuclear weapon would only strengthen and the prospects for a diplomatic solution more remote.

The only way to make absolutely certain Iran did not develop a nuclear weapon would require not just airstrikes, but more comprehensive combat operations attacking Iran’s broader infrastructure network – something that would destroy Iran’s existing nuclear infrastructure as well as its near-term potential to re-build. The odds of this president—or any future one—preemptively attacking Iran on such a scale are remote.

More likely, with diplomacy exhausted and military action as the only option, the United States would reluctantly accept the fait accompli of a nuclear Iran and begin efforts to contain it. This is the true consequence of no deal with Iran. The choice was not “deal or war,” but rather “deal or acceptance.”

Does all this mean the United States needed the deal as badly as Iran? The failure to reach a peacetime negotiated solution would have put the United States in a tough spot: accept a nuclear Iran and watch the NPT and the international nonproliferation regime slowly unravel, making the entire world more dangerous, or go to war. This deal, if it proves effective, certainly saves the United States a lot of trouble. On balance then, the nuclear deal makes sense.

There are caveats, of course. The deal limits Iran’s nuclear program for only 10-15 years and its success depends on effective monitoring and the resolve to punish cheating. The Harvard Belfer Center for Science in International Affairs nicely summarizes the deal’s potential and its limits:

If Iran complies, the JCPOA buys at least 10 to 15 years before Tehran can significantly expand its nuclear capabilities. If Iran cheats during this period, JCPOA monitoring and national intelligence are likely to detect major violations, which would enhance U.S. and international options to intensify sanctions and take military action if necessary. If the agreement survives after 15 years, Iran will be able to expand its nuclear program to create more practical overt and covert nuclear weapons options. There are different views on whether the JCPOA will create conditions that help to reduce Iran’s incentives to pursue nuclear weapons in the long term.

The deal will only be as strong as the IAEA inspections and the ability of the U.S. intelligence community to monitor Iran’s adherence. It will only be as strong as the United States’ ability and willingness to enforce consequences for cheating. But gathering intelligence on Iran will be all the easier with the eyes on the ground the deal provides for. Reacting to potential cheating will only be easier with the one-year breakout time created by the deal, compared to the world of no deal in which the U.S. only has two months to both detect a breakout attempt and organize an effective response.

Looking Forward

There is little doubt that reducing sanctions and perhaps eventually normalizing Iran’s international standing enhances Iran’s strategic position. In signing the JCPOA, the Obama administration is making a calculated trade-off: exchanging a reduction in existential risk for an increase in conventional risk. The deal reduces Iran’s ability to become a nuclear power while enhancing its ability to exercise conventional power.

The pause on Iran’s nuclear program and its reduction of the existential risk embodied in a nuclear weapon is the only merit upon which to judge the JCPOA. Any other argument related to Iran’s approach to wielding conventional military and economic influence – that the agreement will nudge the Iranian government to moderate over time, that more economic connectedness reduces the likelihood of war, that the deal is the cornerstone of a transformation of Middle Eastern geopolitics in favor of peace and stability – is misguided. A talented rhetorician could make a case for these, but these are cases built on hopes pinned to an optimistic interpretation of the deal’s possible second- and third-order ripple effects. Iran has only made nuclear commitments. Any other argument for the deal is nice but irrelevant in an assessment of its merits.

The existential-conventional trade-off makes sense for the United States, which can only be threatened in any material sense by Iran if Iran is nuclear armed. But the United States has allies in the Middle East who will face the consequences of an Iran with increased space for conventional action, leading to mismatched assessments of the deal’s impact on regional security. The Obama administration seems ill prepared for this reality.

The ongoing war in Yemen is a great example of the environment of elevated conventional risk in the Middle East and how the Iran deal complicates America’s diplomatic relationships in the region.

In the spring of 2015 a coalition of mostly Arab states led by Saudi Arabia and featuring significant contribution from the United Arab Emirates intervened in Yemen after an insurgent faction, whom the Saudis and Emiratis claim is an Iranian proxy, took over the government. The United States has provided the intervention with intelligence, munitions, and logistical support. Now a year and half old, the war has created a humanitarian disaster while making only minimal progress toward the coalition’s political goal of restoring Yemen’s former government.

Why exactly did the United States find itself supporting a Gulf Arab war that has achieved little, at immense human cost, and has no direct bearing on American national security? Likely because the Obama administration underestimated just how threatened the Gulf states felt by the Iran nuclear deal. With the nuclear deal trending toward completion, the desire to demonstrate resolve in the face of perceived Iranian expansionism in the Arabian Peninsula was a major factor in the Saudi and Emirati decision to go to war. Obama likely threw America’s support behind the war in Yemen because he felt the need to concretely reassure America’s Gulf allies that Washington is still seriously committed to Gulf Arab security despite his administration’s outreach to Tehran.

As the war in Yemen intensified in early 2015, a State Department official told Politico that “you can dwell on Yemen, or you can recognize that we’re one agreement away from a game-changing, legacy-setting nuclear accord on Iran that tackles what everyone agrees is the biggest threat to the region.”

This statement highlights the gap between Washington and some of its Gulf allies; it demonstrates a failure to appreciate that for Iran’s immediate neighbors the deal hardly lessens the conventional threat Iran is perceived to represent and, pinned to a misplaced hope that the deal will lessen Iran’s role in non-nuclear conflicts, suggests a lack of planning for how to mitigate negative reaction to the deal.

First Step to Getting out of the Middle East Quagmire?

Some analysts have argued that the Iran deal is part of a broader Obama administration effort to shift American foreign policy energy and resources away from quagmires in the Middle East toward engagement with rising powers in Asia, taking a “long view” of how power is shifting in the world geopolitically.

Perhaps contrary to the administration’s hopes, the JCPOA does not free the United States from Middle Eastern entanglement – not if the United States hopes to help mitigate the deal’s potential conventional consequences. The United States must remain intimately engaged in the region, not just to monitor Iranian compliance with the JCPOA but also to manage the increased risk of conventional war emanating either from an emboldened Iran or from the defensive reactions of America’s traditional Gulf allies. This does not mean the United States must take part in every flare-up, but intensive diplomatic engagement is required if the United States wishes to prevent conventional conflict.

With the JCPOA in effect, the hard part begins. The United States now has ten years to ensure that the end of the deal’s term does not simply reset the world the tense state of 2012, with Iran once again on the cusp of obtaining enough weapons-grade nuclear material for a bomb. Iran’s potential re-integration into the formal international economy will only complicate matters, increasing Iran’s capacity for conventional conflict in the Middle East at a time of great regional volatility. Is the United States prepared to manage what comes next?